American Baroque Period

American furniture in the early to mid-1700s was typically characterized by graceful curves (such as S-shaped cabriole legs) and limited surface ornament. In later periods, the style has been known as “Queen Anne” (named for the British monarch who reigned 1702-1714) and “American Baroque.” British subjects in America adopted the style, and such fashionable American fine and decorative arts tied colonists to European notions of economic prosperity. The earliest known examples of furniture and silver made in Delaware date to this period and typify America’s early artistic reliance on England. Even as British subjects in America followed European fashions, Great Britain limited its American Colonies’ trade options and political power.

It is likely that a local cabinetmaker made this set of chairs for the Dover residence of merchant Vincent Loockerman. This same cabinetmaker also fashioned another set of compass seat chairs, a corner chair and a dressing table that are also on view in the Biggs. These objects are among the earliest known examples of furniture attributed to a Delaware maker.

ARMCHAIR AND ONE OF SIX SIDE CHAIRS

MAKER UNKNOWN

PROBABLY DOVER, DELAWARE, 1740S–65

WALNUT

GIFT OF SEWELL C. BIGGS; 1992.94.1 & .2

Though popular throughout England and New England, desks on frames were extremely rare in the Mid-Atlantic colonies. The elaborate silhouette of this desk’s skirt, the S-curved, cabriole legs, and so-called “trifid” feet are all decorative ideas borrowed from the British Queen Anne style.

DESK ON FRAME

MAKER UNKNOWN

PHILADELPHIA, 1735–50

WALNUT

SEWELL C. BIGGS BEQUEST; 2004.139

This tall clock is one of the earliest and most decorative Delaware clocks known to exist. The case, with its so-called “sarcophagus” stepped top and pierced and applied decoration, is firmly an expression of the British-influenced Baroque style. George Crow worked in Wilmington and trained two of his sons to be professional clockmakers. George Crow’s brother William (ca. 1715–1758) also was a clockmaker. He worked in nearby Salem, New Jersey, and it is believed that he apprenticed in Philadelphia.

TALL CLOCK

MOVEMENT: GEORGE CROW (WORKING CA. 1740–62)

CASE: PROBABLY AN UNKNOWN PHILADELPHIA

CABINETMAKER

WILMINGTON, DELAWARE, 1745–55

BRASS WORKS; WALNUT, TULIP, POPLAR,

YELLOW PINE

GIFT OF SEWELL C. BIGGS; 1992.76

Joseph Richardson was part of a leading artisanal family in Philadelphia that included several generations of silversmiths. They and a few competitors supplied silver products to the entire region. In Delaware prior to 1750, these competitors included Wessel Alrichs and Johannis Nys. Alrichs worked in New Castle from around 1710 to 1726, and Nys worked in Kent County around 1723 to 1734. Covered drinking vessels became popular additions to American homes of this period and were a symbol of the owner’s wealth and prestige.

TANKARD

JOSEPH RICHARDSON SR. (1711–1784)

PHILADELPHIA, 1740–50

SILVER

GIFT OF SEWELL C. BIGGS; 1994.40

Many American potteries appeared in the colonial period, however, merchants often still imported extremely refined, decorative ceramics like these from European and Asian countries. Laws required American colonists to purchase most of these luxury items from British merchants, benefitting the Crown via taxation.

MILK COWS

NETHERLANDS, 1740–75

TIN-GLAZED EARTHENWARE

SEWELL C. BIGGS BEQUEST; 2004.11–.12

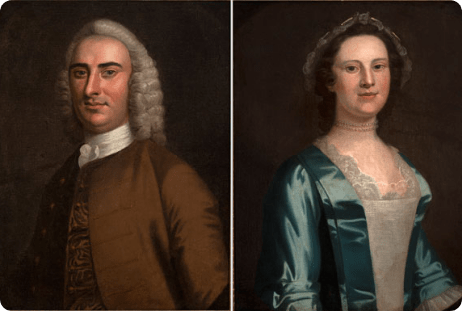

Descended from Dutch colonists in New York, Vincent Loockerman (1722–1785) was a wealthy merchant, slaveholder and landowner who built his home in Dover, Delaware. Today, many of the house’s important 18th- and 19th-century Delaware and Philadelphia furnishings are on view in the Biggs. These objects’ well-recorded history over many years helps tell that of Delaware. They are also a reminder that while some objects were owned by wealthy white families, they also tell the stories of enslaved people who encountered them.

PORTRAIT OF VINCENT LOOCKERMAN

JOHN HESSELIUS (1728/29–1778)

1750S

OIL ON CANVAS

ON LOAN COURTESY OF THE DELAWARE STATE

DIVISION OF HISTORICAL AND CULTURAL

AFFAIRS

Portraits in colonial America were expensive luxuries, so many early portrait painters traveled throughout the colonies to find wealthy enough patrons to make a living. These itinerant artists, known as “limners,” included John Wollaston, who traveled throughout the Delmarva Peninsula, as well as New York, Philadelphia, Virginia, and South Carolina. When these portraits were painted, Brandt Schuyler was deputy mayor of New York.

PORTRAIT OF MARGARETA VAN WYCK SCHUYLER & BRANDT SCHUYLER

JOHN WOLLASTON (WORKING 1742–1775)

1750

OIL ON CANVAS

SEWELL C. BIGGS BEQUEST; 2004.398–.399

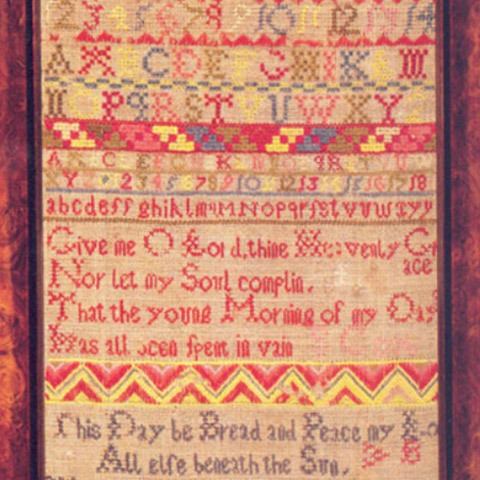

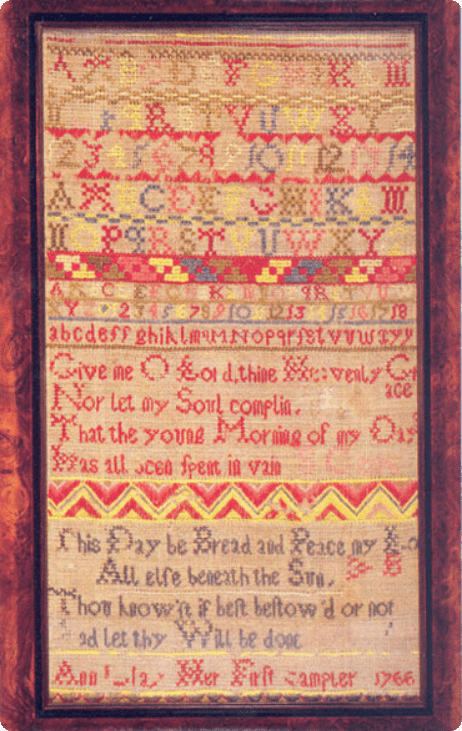

To educate their daughters, prosperous families in colonial Delaware often followed the European tradition and instructed them in domestic and art-related topics. Instead of studying academic courses, girls learned such things as painting, music, and needlework. This example of childhood embroidery is a “sample” of the types of decorative embroidery techniques that girls learned at home or in schools for girls throughout the Delaware and Philadelphia regions.

SAMPLER

ANN CLAY (1759–1846)

NEW CASTLE, DELAWARE, 1766

WORSTED WOOL AND SILK ON LINEN

SEWELL C. BIGGS BEQUEST; 2004.498

Abraham Delanoy studied painting in London under the tutelage of renowned artist Benjamin West. Following the completion of his studies abroad, Delanoy returned to the United States, where he established himself as a portrait painter in New York City, South Carolina, and the West Indies. His portrait of Captain Harding Williams, with its emphasis on linearity and soft tones, is typical of Delanoy’s style. Williams’ trade as a captain of trips to Lisbon, Dublin, Bordeaux and Glasgow, is referenced in this portrait through the inclusion of a map and compass. Captain Williams lived in the Delaware Valley area and is buried in the cemetery of Immanuel Episcopal Church in New Castle, Delaware.

FOR FURTHER THINKING: Delanoy included references to Captain Williams’ trade as a sea captain. What would you included in a portrait of yourself to reference your job and personality?

CAPTAIN HARDING WILLIAMS

ABRAHAM DELANOY (1742-1795)

CA. 1785

OIL ON CANVAS

Duncan Beard was a notable silversmith and clock maker in Odessa, Delaware. In the state’s 1790 censuses, Beard’s profession is listed as “silversmith,” though these four spoons are exceptionally rare surviving examples of his work; however many of his clock faces and movements are known and have sold at auction for record prices. The Biggs’ acquisition of these four spoons ranks us among the largest collectors of Beard’s silverwork in a public collection.

FOR FURTHER THINKING: Do you think it’s important to collect different kinds of works done by the same artist? Why or why not?

FOUR TABLESPOONS

DUNCAN BEARD (UNKNOWN-1797)

CA. 1750

SILVER

MUSEUM PURCHASE

Spice chests, also called spice boxes, were popular in 18th-century America. Surviving examples are mostly from Pennsylvania and the surrounding region, where they were especially prominent. Secured with a lock and key, this chest probably held valuables such as papers and jewelry; spices such as salt, pepper, thyme and rosemary; and exotic imports such as cinnamon and ground ginger. The decoration on the front of this spice cabinet suggests that it was likely displayed prominently in the home. It was probably made to commemorate the wedding of Quaker couple Robert Lamborn (1723-ca. 1801) and Ann Bourne Lamborn (1729-1790) from London Grove Township, Chester County, Pennsylvania, who were married in 1746. The decorative inlay, or marquetry, on the front shows its owners’ initials and the year 1748. The inside of the cabinet has multiple storage drawers of different sizes and a print affixed inside the door that depicts King George III, the British monarch during the American Revolution. The artist and exact date of this print is unknown, and it may be an addition.